About the Author

When my daughter was in third grade, she brought home a list one day that described what everyone in her class wanted to be when they grew up. Most of the kids clearly picked the same jobs their parents held. But a few went for the fantastical. One kid said he wanted to be a spy; another was longing to be a professional dirt-biker; another saw himself as a future movie director. And I looked at that list and thought, “Yep, I’m with the dirt-biker and the spy.”

With my mother and little sister, when I was 6. I already had an older brother and a younger brother when my sister was born, and I was very, very happy to have another girl in the family.

With my mother and little sister, when I was 6. I already had an older brother and a younger brother when my sister was born, and I was very, very happy to have another girl in the family.As a kid, I also longed for a career that I didn’t actually believe real people got to do. The far-out, only-in-your dreams career I wanted was to be an author. All the grown-ups I knew were farmers (like my dad) or nurses (like my mom), teachers or dentists, housewives or grocery store clerks, etc., etc. The only authors I’d ever heard of were, well, just in books.

I grew up on a farm about halfway between two small towns: Washington Court House, Ohio, and Sabina, Ohio. I come from both a long line of farmers, and a long line of bookworms. When we went on family vacations, my parents were always saying things like, “Would you guys stop reading for a minute and look out the window? That’s the Grand Canyon we’re driving past!” But then my mom would laugh and say, “That’s exactly what my parents always said to me when I was a kid!” Now that I’ve made the same kind of comments to my own children (“Please put down Harry Potter for a moment! That’s the Pacific Ocean out there!”), it makes me wonder how far back this goes. How many of my ancestors, immigrating to America, had to admonish their kids, “Would you put down that book and look out? Don’t you want to see our new home?”

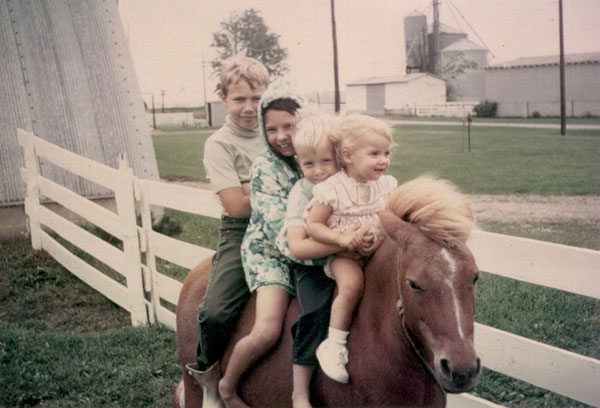

With all my siblings, on our pony Ginger. Since I grew up on a farm, we had lots of animals around. To answer the question a lot of kids ask seeing this picture: Yes, I realize I was wearing a winter coat but no shoes. I didn’t really see the point of shoes when I was 8.

With all my siblings, on our pony Ginger. Since I grew up on a farm, we had lots of animals around. To answer the question a lot of kids ask seeing this picture: Yes, I realize I was wearing a winter coat but no shoes. I didn’t really see the point of shoes when I was 8.The people I met in books always seemed very real to me: as a kid, I counted among my friends the whip-smart New York kids of E.L. Konigsburg books, Harriet the Spy, Anne of Green Gables, Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, Anne Frank, Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, The Little Princess’ Sara Crewe, L.M. Montgomery’s Emily Byrd Starr, Beanie Malone, and many, many others. To me, it didn’t seem to be much of a step to go from loving books to wanting to create books of my own.

With our loyal dog, Lassie. We were not very original naming her, but she was a great dog.

With our loyal dog, Lassie. We were not very original naming her, but she was a great dog.But because I also read more practical information as well—my local newspaper, Time magazine, accounts of the Great Depression—I knew that I couldn’t be completely impractical about my career choice. So I hedged my bets a bit when I went off to college. I did major in creative writing, but I also majored in journalism (and history, just for fun). Except for the summer after my freshman year of college, when I worked as an assistant cook at a 4-H camp (which was lots and lots of fun), every job I’ve held since then has been related to writing in some way. During college, I worked on my school newspaper and had summer internships at newspapers in Urbana, Ohio; Charlotte, North Carolina; and Indianapolis, Indiana. After college, I worked first as a newspaper copy editor in Fort Wayne, Indiana, then quickly moved back to Indianapolis to work as a newspaper reporter there.

I didn’t fully realize it at the time, but during those early years of my life I was also amassing things to write about. During high school, I acted in school plays; played flute and piccolo in the marching, pep and symphonic bands; sang in the school choir; worked on the school newspaper; ran track one year; competed on a school quick-recall team; served on the county junior fair board; and did volunteer work through my church and 4-H clubs. (Lest you think I was some multi-talented prodigy, I should point out that I’m a terrible singer, a terrible actor, and, as a runner, I’m really, really good at walking. One of the advantages of going to a fairly small school is that, if you’re not too afraid of making a fool of yourself, they’ll let you try just about any activity.) In college, one of the best things I did was spend a semester studying in Luxembourg, a small country nestled between France, Germany and Belgium. Living in a foreign country is a great way to force yourself to really think about, “Who am I?” “What shaped me as a person?” “Why do I believe what I believe?” “What do I want out of life?” “What shaped all these people I see around me?” “Why do they believe what they believe?” “What do they want out of life?”

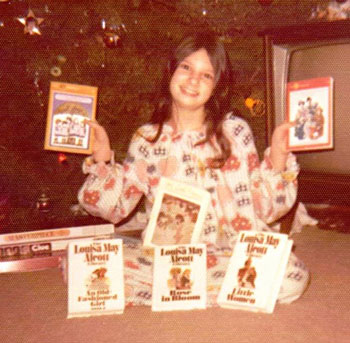

Showing off my favorite Christmas presents, the year I was 10: Louisa May Alcott books, All-of-a-Kind Family books, and A Little Princess. The nightgown I’m wearing was also a gift, made by one of my aunts. She was actually a great seamstress, but none of us knew then how weird the fashions of the 1970s would look decades later.

Showing off my favorite Christmas presents, the year I was 10: Louisa May Alcott books, All-of-a-Kind Family books, and A Little Princess. The nightgown I’m wearing was also a gift, made by one of my aunts. She was actually a great seamstress, but none of us knew then how weird the fashions of the 1970s would look decades later.But it was being a reporter that really gave me the opportunity to meet lots of different people, in vastly different circumstances. It never failed to amaze me that I could sit down with people, and begin asking really, really nosy questions, and because I was from the newspaper, they would almost always answer. For most of my time as a journalist, I worked as a general assignment reporter, which meant that I could be covering a fire one day, a scientific breakthrough the next, a politician’s news conference the next. (Or, on really busy days, some combination of several vastly different events, all at once.) Somehow, for me, hearing so many different stories from so many different people–and witnessing so many different events–didn’t just inspire me to write it all down. It also inspired me to play with different plots and characters and settings in my head. Facts weren’t enough for me. I still also wanted fiction.

For anyone who doesn’t trust journalists, I should point out that I didn’t change any facts for the stories I wrote for the newspaper. But I would go home and also write different kinds of stories, ones based more on my own imagination and my sense that there could be some sort of higher truth than just “facts.” Still, it wasn’t always easy, after spending eight or nine or ten hours a day writing and reporting, to write some more in my time off-work. So during this time, I had a lot more ideas for fiction than I actually wrote down.

Happy to be a sixth grader. In my school district, this meant being at the top of the elementary school, not the bottom of any middle school or junior high.

Happy to be a sixth grader. In my school district, this meant being at the top of the elementary school, not the bottom of any middle school or junior high.It was also during this time that I got married. My husband, Doug, and I met in college, and he also went into journalism right after school. When he got a job as city editor of a newspaper in Danville, Illinois, it seemed like a big complication for my career. If I wanted to continue as a newspaper reporter, I knew I’d probably have to have my husband as a boss. This did not seem like a good idea. My husband and I agreed to see this complication as an opportunity: this would be my chance to concentrate on fiction. I took part-time jobs teaching writing at a community college and doing freelance business writing, but I also wrote Running Out of Time; Don’t You Dare Read This, Mrs. Dunphrey; and numerous short stories. While I was working on those, my husband and I also decided to start a family.

Like most writers, I went through an agonizing phase of submitting my work and collecting nothing but rejection letters for quite a while. For me, this phase lasted long enough that, by the time I sold my first two books (both at once, actually) our daughter, Meredith, was a year and a half old, and I was pregnant with our second child, Connor. Talk about feeling multiply blessed! Still, it was a little challenging to be a newly published author at the same time that I was becoming a new mother. For those first few years, I wrote only during my kids’ naptime, when I probably should have been napping myself. So I developed strict criteria for everything I wrote: it had to be exciting enough to keep me awake.

Showing hogs at the county fair as a teenager. I don’t know many other authors who ever did this!

Showing hogs at the county fair as a teenager. I don’t know many other authors who ever did this!Since then, my life has changed quite a bit. My husband and kids and I moved from Illinois to Clarks Summit, Pennsylvania, to Columbus, Ohio. My kids are now both grown up, and I no longer have to worry that the sound of me typing at the computer might wake them up. But my criteria for what I write hasn’t changed that much. I know I have to write a story when the story keeps me awake at night, teases at the back of my brain all day, just won’t let me go.

And that’s why I became a writer.

Connect with Margaret: