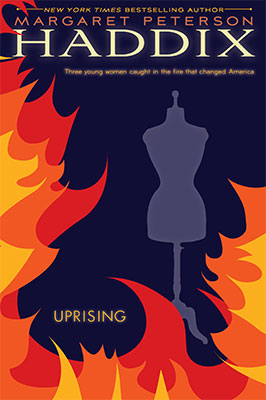

Uprising: Frequently Asked Questions

Note: My answers may contain some spoilers for the book—please don’t read this if you haven’t finished the book!

How much of this is real?

For the most part, I tried very hard to make this book as historically accurate as possible. Partly because I used to be a newspaper reporter, and had to report facts accurately, I felt very strange about knowingly changing any details. One detail I fudged a little bit: in reality, the Triangle factory workers walked out of their jobs for the first time in 1908, about 15 months before the strike began for real. I don’t give an actual date for this event in Uprising, but I kind of made it seem as though it happened only three months before the strike began.

The only details I knowingly changed outright were the names of the factory owner’s daughters. They and their governess really were at the factory the day the fire broke out, and they really did escape from the roof on a ladder leaned up against the building next door. But their names were Henrietta and Mildred rather than Harriet and Millicent. I don’t know what happened to the real girls after the fire, but they were young enough at the time of the fire that it’s very likely that their children and grandchildren (if they had any) are still alive. The girls were not at all responsible for what their father did or how he ran his factory, so I didn’t want to use their real names. Maybe this seems odd to anyone else, but it’s what felt right to me.

How much research did you do for this book?

I spent months doing very little except researching Uprising. I read about immigrants, factories, labor unions, Italian peasants, persecution of Russian Jews, Jewish life, Jewish religion, the strike, the fire, life in the tenements, New York City history, early 1900s clothing, early 1900s food, the women’s suffrage movement in the United States and England, society women in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and several other topics. I had to get help with translations for both Italian and Yiddish. I became completely obsessed.

Why did you switch back and forth between three girls’ viewpoints, instead of telling just one story at a time?

Everything I read about the strike and the fire and the general atmosphere of New York City in the early 1900s made me feel that I had to use multiple viewpoints if I wanted to tell a complete story. I needed each piece—the fervent union sympathizer, the desperate immigrant, the wealthy girl with suffragist leanings—in order to give anything approaching a full perspective. I think we have a tendency to think that the past was simple, because it’s over and done with, and we know how it turned out. (And also, because their technology wasn’t as advanced as ours.) But there were a lot of complicated events and movements and ideas intermixing in the early 1900s, and I didn’t think I could do them justice looking through the eyes of just one character.

Connect with Margaret: